Check Out the Punk Scene

by Osita Nwanevu

All told, I’ve probably spent more hours of my life in libraries than any other kind of place save restaurants. I like libraries because I like books, yes, but I also like them because I like music.

One night my freshman year of high school, I caught an episode of Cold Case that featured tracks from Nirvana—a band I’d heard of, and had maybe even heard in passing before. But that particular evening, the music sounded radically different from anything I’d spent my life listening to up to that point—the oldies and classic rock hits that were always playing in the car or in the house, the Top 40 I’d hear at dances or on the buses to and from school. I wanted to hear more. The library had Nevermind on CD; the next time I went, I checked it out. To date, it’s the most personally consequential item I’ve ever borrowed from a library. It fundamentally rewired me. No book touches it.

I took it to school in my CD player every day. I checked out a Cobain biography and read it three times. I checked out Cobain’s journals and hunted for information about the bands he mentioned. That led me to a website called Pitchfork. I discovered they’d published a book the library had—The Pitchfork 500: Our Guide to the Greatest Songs from Punk to the Present. I checked that out too and listened to every track I could find on YouTube. (I didn’t have an iPod at the time and knew better than to ask for one, or the money to download songs from bands with names like Suicide or the Sex Pistols.) Then I hunted for albums. The library system had a few, seemingly added to their collections at random—Sonic Youth’s first EP, for instance, featuring an amplified electric drill, but not Daydream Nation—and I requested that they order more, writing and submitting little essays about how important these records I’d never actually listened to were, based on what I’d read. And they bought just about everything I asked for, at the public’s expense. I was 14. It was incredible.

One of my biggest regrets from the time I lived in DC, partially because it reminds me of all this, is not having taken the opportunity to explore the DC Public Library’s punk archive—a collection of books and other artifacts from the city’s deeply influential punk scene—music, merch, photos, oral histories, posters—that might otherwise have been lost to time.

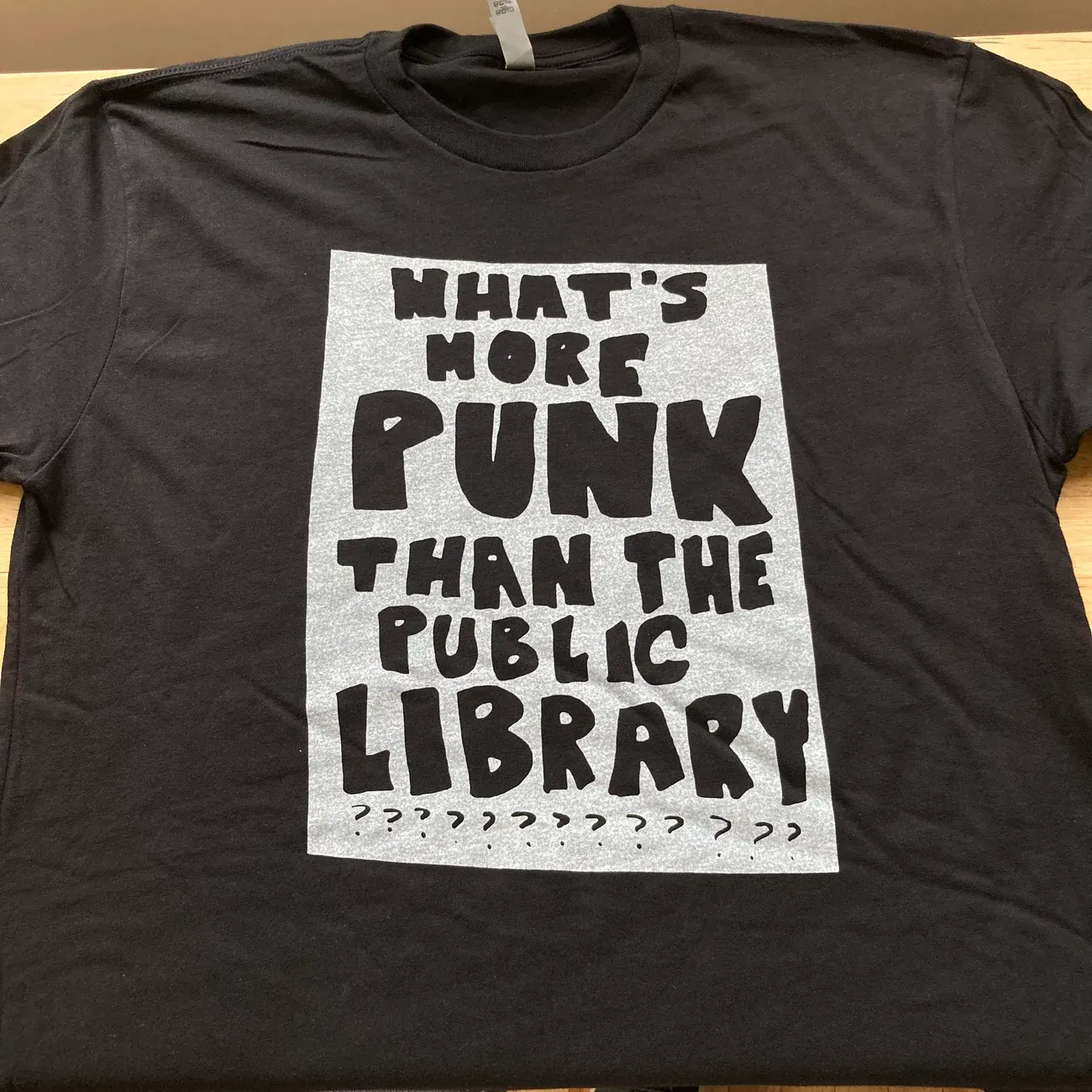

Since 2021, a non-profit that supports one branch of the DC library system has been selling a T-shirt inspired by the archive in the style of an old punk poster—“WHAT’S MORE PUNK,” it reads in block text, “THAN THE PUBLIC LIBRARY?”

Last May, DC resident and blogger Matt Yglesias tweeted that the shirt bothered him. “I saw someone wearing this shirt on the street today,” he wrote. “[A]nd I think the effort to mash up the earnest, stolid, social role of librarian with the chaotic anti-establishment ethos of punk explains a lot of contemporary dysfunction.” Last week, he followed this up with a full post on his Substack, Slow Boring, making the case that public libraries are antithetical to the punk ethos:

At the end of the day, if you want a public library that has a good local punk scene archive, you need to get a building built. You need to ensure the collection is stored properly. You need rules about who can access the collection and under what terms. The library itself should be comfortable and well-maintained, and pleasant to use for most people, not only a refuge of last resort for the most marginal members of society. That means you’re going to need standards of conduct inside the library and enforcement and punishment for people who break the rules. It’s all good stuff—but it’s not very punk rock.

According to Yglesias, the punk ethos is best exemplified by songs like The Living End’s “Prisoners of Society”:

Well we don't need no one to tell us what to do

Oh yes, we're on our own and there's nothing you can do

So we don't need no one like you to tell us what to do

“[B]eyond lyrics, there’s something convenient about being in such a decided minority that you never need to actually run things,” he writes. “If someone puts you in charge of a public institution—whether that’s a transit system or a library or a school or Medicare—you end up dealing with tradeoffs and troublemakers and questions like ‘how much should the curriculum reflect what I personally believe versus what the random parents at this school want us to teach?’ It’s in many ways a big drag.”

The post is instructively confused on a few points. While the deathless and tedious question of what punk is will never be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, Yglesias is right that the music and the lifestyles that accompany it are generally shaped by an anti-establishment sensibility. But there’s a difference between being anti-establishment—opposing society as it exists at present—and being against rules, authority, and order, in principle. In fact, in both their music and their political activity, many punk artists have made the case that the structures and institutions that shape our society should be replaced not by chaos, but by structures and institutions that are more righteous, by their lights—from punks with conventional socialist and social democratic politics on the left (perhaps most famously The Clash), to the widely reviled punks on the right who pine for fascism. The genre’s politics are a messy, fascinating jumble; you’ll learn more about them at your local library than you will from Yglesias’s piece.

What Yglesias offers instead is a simple bifurcation. In radical politics, there are socialists, who, as much as Yglesias might disagree with them, believe in constructive activity, and there are anarchists (an intellectual tradition, his post suggests, that encompasses both Green Day and Mikhail Bakunin) who don’t really believe in anything beyond tearing institutions down by any means necessary. The latter frame of mind, he argues, has infected the contemporary left. “Most of the energy on the left in recent years,” he writes, “has been aimed at delegitimizing existing structures and hierarchies and calling into question the legitimacy of enforcing rules.” But this picture of anarchist thought and practice—no bedtime, plus political assassinations—is a caricature.

Some of the best evidence on this front comes, actually, from the punk rock scene. Any touring musician or concert promoter or record producer will tell you that the project of making and sharing music of any kind involves constructive compromises, financial acumen, technical know-how, and a willingness to tolerate hours of interminable but essential tedium. You need venues and recording studios. You need either labels willing to put out your music, or the resources and diligence to do it yourself. Precisely because of the anti-establishment nature of their music, punks had to build much of this infrastructure from scratch; the genre itself is a miracle of cultural organization, undertaken with scarce resources by artists and fans operating at or near society’s margins. Touring circuits were mapped out. Zines were distributed. Radio stations were founded. People bought the paper for flyers and the blank cassette tapes, with money someone was keeping track of; I’d wager that many of the punks managing squats and performance spaces at varying levels of legality in DC in the 80s and 90s were as least as familiar with the city’s zoning and occupancy regulations as Yglesias is. There were anarchist punks at the heart of all this. There still are.

Ironically, the DC scene documented in the punk archive was especially distinctive for the rules many of its members lived by. Influential straight edge bands like Minor Threat promoted a substance- and vice-free lifestyle, and popularized a now widely used system to allow underage fans to see shows without being served alcohol. And for decades now, punks there and elsewhere have worked to institute formal and informal codes of conduct to protect the safety of fans and concertgoers, including women, racial minorities, and the queer community. All told, the seeming chaos of the mosh pit was made possible to begin through organizations, structures, and rules crafted and tended to by members of a deeply committed subculture. This is exactly the temperament libraries depend upon. And the library boosters actually responsible for the T-shirt that’s so troubled Yglesias said as much to the Washington Post in 2021:

Carlos Izurieta, president of Mount Pleasant Library Friends, a nonprofit organization that supports the public library, said fellow library supporters made the first shirt for him in March as a gag birthday gift. Izurieta, who grew up attending punk shows and playing in bands, saw many links between a genre that prides itself on do-it-yourselfism and a public institution that provides free resources to one and all.

“Punk in D.C. is centered around the local community,” he said. “I feel like the library is like that. It’s a place for people to go who don’t have access.”

The shirt was inspired by a flier that D.C. librarian Chelsea Kirkland created with a version of the slogan while tabling for the library at the D.C. Punk Rock Flea Market, an annual all-things-punk sale held at a nearby church.

Kirkland, 36, grew up in the San Francisco area and said the punk community was her “whole world.” When she started going to the public library as an adult, she felt her musical and bibliographic communities had a lot in common: There was access to unlimited information, but there was no need to buy anything. This sense of possibility eventually inspired her to get her library degree, she said.

“It’s an open-ended space,” she said of the library. “No one is going to tell you what to do when you’re in there.”

As Yglesias himself concedes, the public library—a communal collection of books and materials made freely available to all—stands “as a kind of alternative to mainstream capitalism” And as a matter of social politics, politicians on the right are going out of their way to make libraries seem dangerous again—the concept of letting anyone read whatever they’d like with taxpayer dollars hasn’t been this subversive and frightening to large segments of the American public in quite some time. To say, nevertheless, that libraries aren’t very punk rock’—that they contradict the ethos of the genre and scene merely because they require organization and administration —is to say that punk itself, which needs organization and administration no less, is not very punk rock. That’s not tenable unless one makes Yglesias’ mistake of losing sight of the ethics or politics underneath a given aesthetic.

Mount Pleasant Library Friends t-shirts are still available.